(Originally published to Glitchwave on 3/12/2023)

[Image from giantbomb.com]

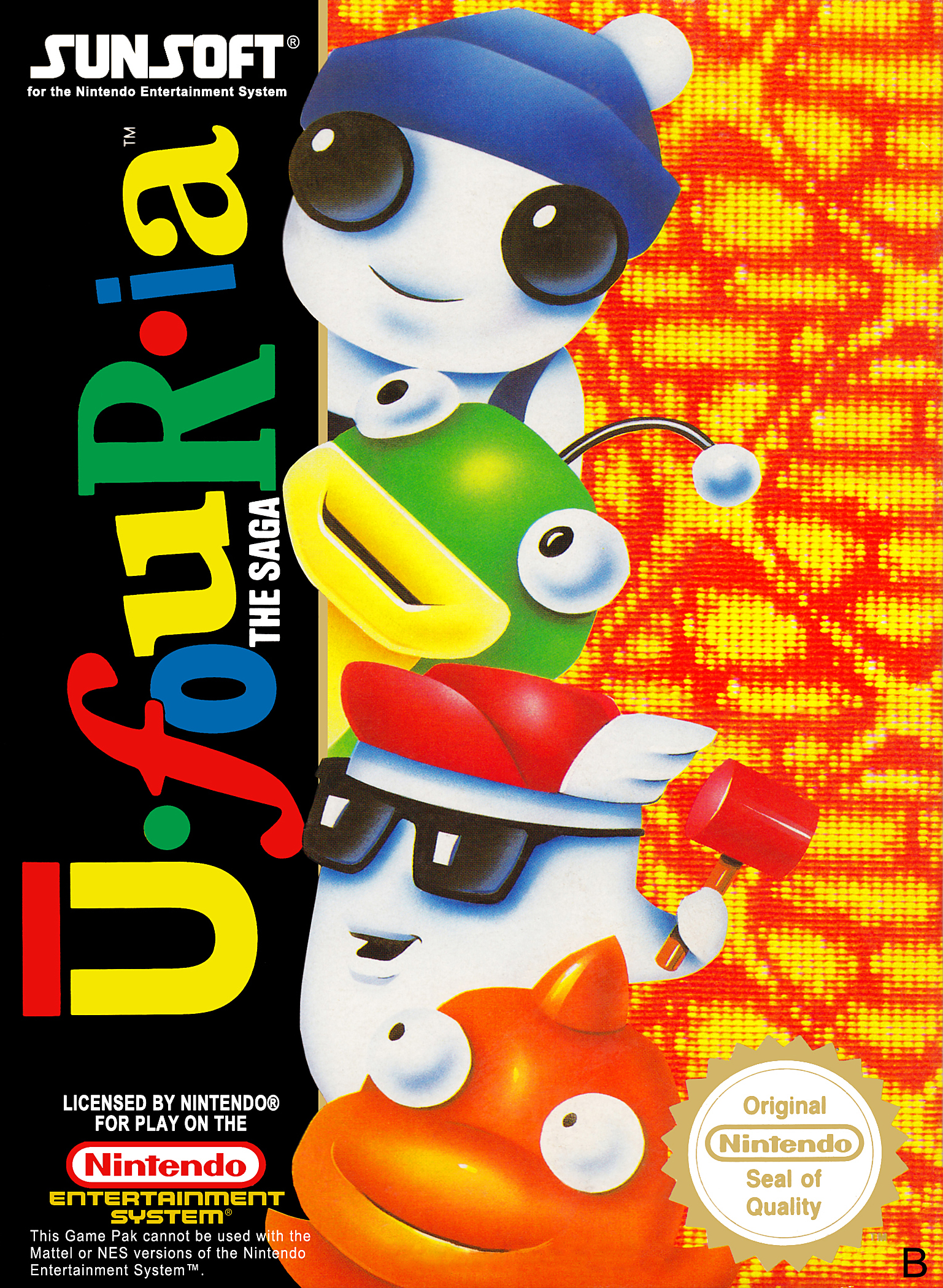

Ufouria: The Saga/Hebreke

Developer: Sunsoft

Publisher: Sunsoft

Genre(s): Metroidvania

Platforms: NES

Release Date: September 20, 1991

“Alex Kidd on acid” should’ve been the tagline for Ufouria: The Saga. The similarities between the game and Sega’s pre-Sonic hit on the Master System fall on their bright aesthetic and more methodical approach to a 2D platformer’s pacing. Those comparisons end when Ufouria takes the twee, childish whimsy of Alex Kidd and dips it head first in a lysergic liquid and totally trips balls. A group from the land of Ufouria gets lost and separated in a strange land, and one of the four friends must retrieve the rest of them and set a course back home. Although the premise is simple, I neglected to mention that the savior is a snowman searching for a dragon, a ghost, and an anglerfish. Also, it’s worth mentioning that some of the platforms that the snowman must hop onto to hold his ground are colored faces that look up with a deranged, closed smiles. Some platforms lend a hand in letting the player climb upward by providing a drooping strand of saliva viscous enough to hold, and the creatures that offer flight assistance look like the abominable lovechild of a chicken fetus and a Teletubby. Enemies range from blobs, clowns, detached lips with long tongues, frog statues, crows that drop anvils, etc. The consistent factor with this eclectic range of enemy types is that upon defeating them, something that resembles a molested-looking pillow pops out from their remnants which the player can use as a projectile weapon. By my interpretation, it might be the soul of the enemy, but it’s hurting my brain attempting to make sense of it. If not for the complications of using licensed music, an 8-bit rendition of Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” should play on a loop throughout the game. The hallucinatory, Japanese weirdness of Ufouria is a charming factor that makes it aesthetically interesting.

Ufouria’s cast of strange characters is the crux of the game’s Metroidvania design. Following the path of least resistance the beanie-wearing Bop-Louie can traverse will lead to a battle with one of his friends, whose hostility towards him stems from amnesia. Once Bop-Louie literally knocks some sense into them, they join the party for the duration of the game. Once unlocked, each partner can use their distinctive talents to uncover the hidden areas that Bop-Louie cannot access. Freeon-Leon’s scaly, orange body is the only one adhesive enough to naturally walk on the ice without slipping, and he can swim on any water’s surface if a pool lies between gaps of land. The cool Mr. Shades uses his weightless, incorporeal form to glide across gaps, and the bulbous Gil’s gravitational grip on the water allows him to submerge himself in any body of it like he was walking. Bop-Louie isn’t made irrelevant by his friends either as he is eventually granted the ability to scale up any surface like climbing a ladder. All of them also have specific extra abilities for either traversal or combat. For example, Bop-Louie can retract his head like a spring to hit enemies at a distance, and Gil’s egg-shaped bombs that he coughs up are essential to breaking the brick walls that inhibit the end-game collectibles. None of the characters stop being useful, as they are all distinctive enough to provide a special service (even if Gil’s swimming ability is more proficient than Freeon-Leon’s). I wish I didn’t have to keep pausing the game to select one but considering how primeval the notion of playing as multiple characters was in the NES days, I’ll accept the slightly inconvenient process. At least it’s less tedious than the character swapping in Castlevania III, whose glacial shift felt so long that it should’ve been accompanied by elevator music. The big question of why the designs of Bop-Louie and Freeon Leon have been changed in the international versions from a penguin and a guy in a catsuit is unclear. Perhaps a human being wouldn’t have been as weird, and kids would find an adorable penguin with a detachable head to be unsettling as opposed to the more…biodegradable, transient snowman?

In the first Metroid on the NES, the game’s sense of directing the player through an environment with a nonlinear world design felt a little too amorphous to uphold what would become the Metroidvania design philosophy. I thought that Ufouria would be subject to the same lack of form, as I attributed Metroid’s sparseness to the unadorned hardware of the NES. Fortunately, Ufouria proved to me that developers didn’t need a successive console generation for the Metroidvania genre to blossom to its ingenious potential. Ufouria effectively arranges its progression into something readily recognizable as a Metroidvania title. An arrow will point out the path the player is intended to travel on when the game begins, which would compromise on the subtleties that make the genre so enticing. After a certain point, the game leaves the player to their own devices, so the first few moments of hand-holding can be forgiven for an early title. The game makes it abundantly clear which of the four characters is applicable to an obstacle or situation, and a map is even offered as a navigational aid. The map may be primitively rendered with gray blocks representing the layout but considering the Metroid genesis point of the genre didn’t offer one, it’s a monumental leap in progress.

Ufouria’s inaccessible jaggedness stems from a few choices that are as bizarre as its presentation. Evidently, one of Ufouria’s biggest influences was the first Legend of Zelda, and these apparent influences did not translate well. Checkpoints are essential to the world design of the Metroidvania game, as finding these places of respite are great rewards for exploration to relieve the player. Ufouria offers a password system, which I find especially inappropriate and dysfunctional for this kind of game despite its ubiquity in the NES era. However, this isn’t even the prime grievance relating to the game’s method of saving the player’s progress. When the player dies, they are transported back to square one where the adventure started, with everything done up to then still saved at least. It works in The Legend of Zelda because the land of Hyrule was small and densely mapped. In a game like Ufouria, however, where the world is vast and requires the select talents of four different characters, walking back to the place where the penalty was enacted is such a slog. The player’s maximum health can be enhanced with items found on the field similar to Zelda’s heart containers, but collecting one does not fully replenish those containers. The player will most likely find themselves around the starting, depleted level of health, and the nuggets of health that spawn out of enemies only increase it by the quantity of a crumb. It isn’t a problem as the enemies are facile products of the environment rather than animalistic savages. That is, until the final boss of the game, which finds the player having to grind immensely to fill those containers in preparation.

Ufouria’s combat is just as unyielding. The player can always throw the perturbed soul cushions, but a simpler way is to channel Mario and flatten enemies like pancakes with their feet. What the game doesn’t tell the player is that they must hold down on the D-Pad to engage the stomping position, lest they take damage. It seems simple, yet how the player intended to figure this out and not see it as a penalty is beyond me. It oversteps the practice of trial and error a bit. Even though this is the more straightforward method of disposing of the land’s wacky inhabitants, pillow-throwing is the only way to dispose of bosses. Jumping on the heads of the naked, wide-eyed, big-lipped purple bosses to then chuck the hefty bag at them takes place for all the bosses, even though each one of them is intended for each of the four playable characters. Even the final boss is a slightly deviated variant of this. The process becomes too formulaic to hold any real engagement.

Ufouria: The Saga surprised me in more ways than one. The Japanese producers at Sunsoft probably thought that the bizarre presentation and progression of the early Metroidvania that hadn’t been solidified quite yet would be too disorienting for us North Americans, so they deferred it from our soil until the game was a peculiar relic of gaming’s past. While this decision most likely prohibited the title from achieving considerable success, I’m somewhat glad that the game serves as a point of reference in the evolution of one of my favorite video game genres. Despite it being released before Super Metroid and Symphony of the Night, I wouldn’t classify Ufouria as a “proto-Metroidvania” game. While the fabric of Ufouria still shares the rudimentary properties that stain the NES era, it’s incredibly impressive that everything in its foundation still sustains the modern definition of a Metroidvania. With its offbeat quirks and charming outlandishness, this NES oddity shouldn’t be forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment