(Originally published to Glitchwave on 3/28/2023)

Super Smash Bros. Brawl

Developer: Hal Laboratory, Sora, Game Arts

Publisher: Nintendo

Genre(s): Fighting, Beat em' Up

Platforms: Wii

Release Date: January 31, 2008

I also had to hold that sense of anticipation for a long time after that because Nintendo kept blue-balling me with a series of delays. Brawl was granted a more lenient window of development time compared to Melee, much to the relief of creative director Masahiro Sakurai, who could’ve succumbed to a stress-induced aneurysm during the strenuous development cycle of the previous game. As much as I value the mental well-being of this brilliant man, pre-teen me still pouted and groaned at every announcement that Brawl was still in production. Finally, in early 2008, Sakurai added the finishing touches to his next masterwork, and voila: actually playing Brawl was a tangible prospect, and it was so close to me that I could taste it. Once my wistful dream became a reality after yearning patiently for two years, Brawl fully delivered on my wild expectations and became my cardinal game when I got a hankering for some Smash Bros for a lengthy stretch of time. I briefly returned to Melee on occasion, but Brawl simply offered more content to keep me enamored with it.

However, I seemed to be in the minority as others who waited for Brawl with bated breath absorbed the fresh lark of the new Smash Bros. experience on the Wii and quickly reverted back to permanently playing Melee, saying sayonara to Brawl indefinitely. You see Brawl is the first Smash Bros. entry that fans labeled as a regression in overall quality. The wonderful accident that was Melee inadvertently became the pinnacle of Smash Bros. fighting mechanics, much to the chagrin of Nintendo who wanted their collective IP kerfuffle to be as approachable as humanly possible. The less strained development time gave Sakurai the opportunity to shape Brawl into the Smash game that Nintendo wanted, which probably would’ve been an agreeable product if Melee hadn’t blown off the hinges of accessibility to give free rein for hardcore fighting game fans to flourish. Funny enough, Brawl’s legacy was legitimized via a now-defunct fan-made mod titled “Project M,” which is essentially Brawl with the mechanics of Melee. Since that mod was unsurprisingly eradicated by Nintendo, fans are simply content with Melee or any of the newer Smash titles since Brawl’s release. I find Brawl’s negative retroactive reputation to be unfair. Admittedly, Melee is the superior fighting game, but to claim that the franchise’s potential peaked at its second entry is ridiculous. At its core, the prerogative of Super Smash Bros. is to celebrate Nintendo as the most recognizable brand in the gaming industry. Because the company has a storied history and keeps releasing titles of IPs new and old between the years of each Smash Bros. game, Brawl’s obligation to chronicle Nintendo’s recent achievements still meant that the game inherently still had something to offer.

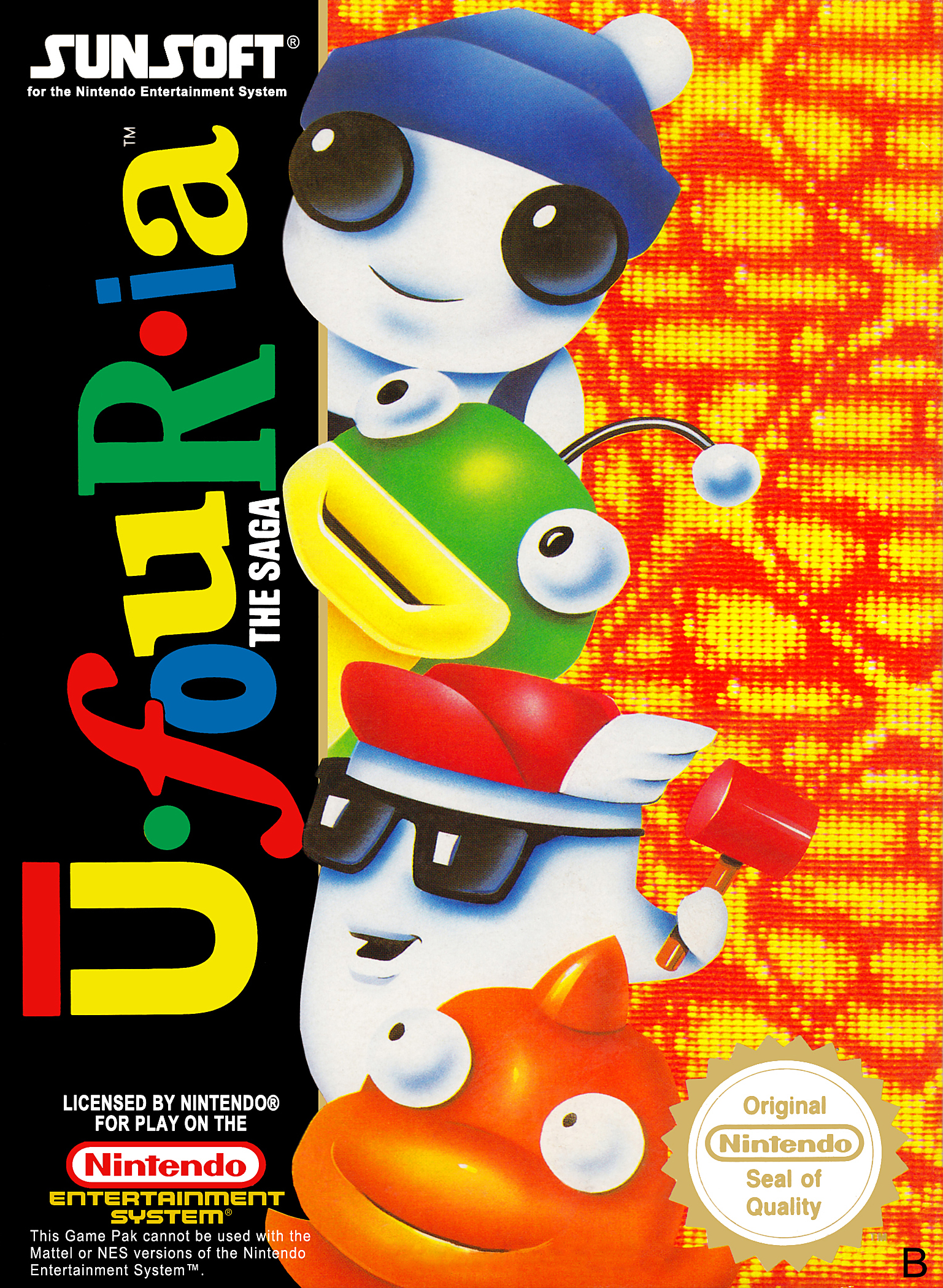

What better way to expound on the previous Smash Bros. title than to add more characters into the fray? At this point in the series, one could argue that Melee included all of the remaining essentials that should’ve been represented in the first game, plus a handful of esoteric relics and exclusive eastern characters thrown in to befuddle us, westerners. While every new inclusion to the Smash Bros. family is a blessing (except for Pichu), the types of characters in consideration tend to fall into a select number of categories. Firstly, there’s the matter of new prime protagonists to represent the IPs that have been created since the release of the last Smash Bros. title. Sadly, Olimar from Pikmin seems to be the only representative here from an IP that debuted on the Gamecube. Characters that emerged on the Gamecube from pre-existing franchises such as the westernized Fire Emblem protagonist Ike and Link’s cel-shaded self from The Wind Waker make their first appearance, but is this really all the Gamecube has to offer in terms of new IP representation? Personally, I’d be over the hill if I got the chance to whack Mario with the power cord of a proportionally-sized Chibi Robo, but I digress. Wario technically counts as a representative from the then-new WarioWare franchise, as his base look is his biker-clad outfit as opposed to his yellow and purple garb that mirrors Mario. Secondly, there’s the initiative to expand the presence of a franchise of a Smash veteran who’s been acting as a lone wolf up until now. Meta Knight and King Dedede are no-brainers from Kirby, Wolf from Star Fox fills in the much-needed presence of Nintendo’s antagonists in the roster, and how long can Donkey Kong go without having his little buddy Diddy Kong by his side (Fun fact: Diddy is also the first Smash character not to have been made by a Japanese developer. True shit)? Pokemon’s presence in the roster was already quite abundant, but the addition of a Pokemon Trainer plays with a loophole that lets the player shift between Squirtle, Ivysaur, and Charizard on one character slot. Pokemon Nintendo evidently fumbled awkwardly around adding more characters from Metroid as their solution was to shift Samus from her distinguishing power suit to her exposed Zero Suit from Metroid: Zero Mission, whose skin-tight material leaves nothing to the imagination (but I’m not complaining!). Thirdly, the position of unearthed, obscure artifact joining the likes of Ice Climbers and Mr. Game and Watch is Pit and R.O.B., a protagonist from the NES who hadn’t been graced by Nintendo’s light since 1991 and a haphazard NES peripheral respectively. Lucas manages to fit every category simultaneously as the most recent character of the bunch at the time and the second character from the Mother series from a Japanese exclusive title that no one in the west is (legally) allowed to play. Tsk-tsk, Nintendo, you fucking tease. Brawl also marks the first Smash game to omit a few fighters from past titles, namely redundant clones such as Dr. Mario and Pichu. I guess Mewtwo and Young Link were replaced by Lucario and Toon Link as more updated representatives. I’m terribly sorry if Roy was your boy in Melee, though.

Already, the Brawl lineup of playable characters surpasses Melees in both quantity and quality. In addition to increasing the stacked roster by the three tenets, Brawl surpasses the potential of Melee’s cast of playable characters by adding a fourth category that really pumped everyone’s nads. For the first time in Smash Bros. history, third-party characters were assorted into the mix. This remarkable new privilege enraptured all of us eager Smash fans as the possibilities seemed extraordinary, but everyone’s expectations were at least reasonable back then. The two visitors to Nintendoland with VIP passes were Konami’s Solid Snake from Metal Gear Solid and Sega’s blue wonder Sonic the Hedgehog. Finally, the fans of Nintendo and Sega could duke it out as their system of choice’s mascot and settle the score. In execution, however, these star-studded visitors weren’t treated with the same level of love by the developers as their own children. Snake’s projectile-latent moveset is more obtuse to operate than any other character’s, and Sonic repeating his classic spin dash for at least three attack variations is the epitome of undercooked. It’s a damn shame, but their novel place in the game is still welcome for obvious reasons.

If every Smash Bros. game is an updated exhibit of Nintendo’s growing lineage, then Brawl was sorely needed in this regard. It’s almost hard to believe that Brawl is a Wii game, or perhaps conversely, it’s hard to believe that Melee is a Gamecube game. Releasing at the Gamecube’s infancy meant that Melee could only chronicle all of the Nintendo releases before the console’s launch, with a few properties from fellow early releases like Luigi’s Mansion and Animal Crossing featured as trophies as “sneak previews.” An entire console generation had passed and then some between Melee and Brawl, so there was a plethora of material to include, even if Nintendo would have you believe that the “lukewarm reception” of the Gamecube era bankrupted the company. While the entire roster may not bolster the past six years accordingly, Brawl’s new stages carry the sense that much has happened since Melee’s release. The entire hub of Isle Delfino, Mario’s mishap-filled vacation destination from Sunshine, is fully displayed via a floating stage with platforms stopping periodically like the player is being given a grand tour. The eponymous setting from Luigi’s solo adventure is seated on a perilous peak as the characters fight in its murky mezzanines. A number of rooms are detailed exquisitely, and knocking at its support beams will make the eerie estate crumble like the house of Usher. Sailing on Tetra’s pirate ship in a cel-shaded sea and being interrupted by the stampede of King Bulbin on the Bridge of Eldin speak for both mainline Zelda games on the Gamecube, and the cylindrical stage of the tutorial boss from Metroid Prime makes a distinction from Prime to the other Metroid titles. The stage itself is kind of lame, however, with the grotesque Parasite Queen in the background as the stage while it occasionally flips.

Now that I mention it, Brawl has the most divisive batch of new stages out of all the Smash Bros. titles thus far. I’d consider “The Pirate Ship”, “Delfino Plaza”, and “Pictochat” to be some of the finest Nintendo-themed arenas for their characters to fight in, but too many of Brawl’s stages are egregiously designed in one way or another. The auto-scrolling of “Rumble Falls” is just another case of the maligned “Icicle Mountain” from Melee, and it’s not any better when the screen is scrolling horizontally in the depleted-looking World 1-1 replica of “Mushroomy Kingdom.” I’d be hard-pressed to refer to the loyal Donkey Kong arcade tribute “75m” and the psychedelic “Hanenbow” as stages because they lack any solid ground, and I’m an unapologetic Poke Floats defender. “New Pork City” takes the sprawling design aspect from the “Hyrule Temple” stage and bloats it to the point where the characters are microscopic under the scope of the dystopian city. Both Norfair and Spear Pillar have hazards that are far too deadly to dance around. No wonder everyone seems to love the simplistic aerial Animal Crossing town view stage “Smashville.” The only new stage that emulates a chaotic Smash stage well is “WarioWare Inc.” which integrates the random microgame lobby from the series with a Smash stage ingeniously.

Several people have already aired their grievances about Brawl's obvious shortcomings, so I’ll keep them brief. Yes, the combat is floatier and fosters defensive play to a fault. Also, I’m sure the person on the development team who conjured up the bafflingly ill-conceived tripping mechanic has been fired and tried for his crimes as harshly as the Nazis in Nuremberg. I share the same negative sentiments with both of these controversies, but my specific qualm that has gone unnoticed by most pertains to the items that were introduced. Adding new characters will always be acceptable, for the player can only play as one character at a time. However, in the case of adding more tools into the mix, the controlled chaos of combat oversteps its bounds. Running into a Bob-omb in Melee made everyone panic but now, Mario’s enemy is joined by the Smart Bomb from Star Fox, whose impact is more extensive than the blunt force of the walking explosive. Wrecking Crew’s hammer is also joined by its more bourgeois brother, the Golden Hammer, which comes with its own separate gag and jingle along with dealing far more damage. The Pokemon selection that appears has been updated to feature Pokemon from both Ruby/Sapphire and Diamond/Pearl, and the number of legendary types with overpowered attacks has only been added onto to increase the likelihood of having to duck and cover from their deadliness. On top of the Pokeballs, a new item called an Assist Trophy appears in an opaque trophy stand to aid the player in battle when summoned. The only difference is that the figure that pops out could be a character from a number of franchises, such as the original iteration of Andross, Ness’s nerd friend Jeff, and even characters whose franchises aren’t represented in the roster like Isaac from Golden Sun. It’s a consolation prize to be featured in a Smash Bros. game despite their relative insignificance. Like the Pokeballs, many of these Assist Trophies are far too capable of doing massive damage, and I’m convinced some like the screen-dominating Nintendog and Mr. Resetti were included to troll the player. Not a great pitch for the new idea, Nintendo.

Among all of these new items used to blast Nintendo’s characters to kingdom come is the cherry on top of the chaos. Once or twice in battle, a floating Smash Bros. logo will materialize and float aimlessly around the stage, accompanied by the gasps of the audience to signify its immense power. Catching the logo and breaking it open will unlock a character’s “Final Smash,” a super move that deals an astronomical amount of damage when the player presses the B button. Some are a wide burst of energy like Mario’s inferno and Samus's cannon blast, others are controlled manually like the three Star Fox tanks and Wario’s stronger garlic-chomping alter ego, and some need precision like Link’s Triforce combo and Captain Falcon running you down with the Blue Falcon. Others such as Donkey Kong’s tepid jam band bongo playing and Luigi’s psychedelic dance feel like the developers slapped some of these onto the characters without any real consideration. My overall point with the new items, especially the Final Smash balls, is that the use of items can now give one player an unfair advantage over the other. One could argue that this was the same case for the items in the previous games and that discussing the items in a Smash Bros. game is superfluous because only scrubs keep them on. As someone who didn’t mind the items in small doses, the alarming rate of easy-to-obtain weapons of mass destruction is unfair. It's another mark of the developers making Smash Bros. more frivolous, but I’m never amused when I lose my winning lead to one of these damned things.

Besides the standard brawling, if you will, is a bevy of extra content that supplements every Smash Bros. game. Classic Mode is still a random roulette of characters until the player reaches the apex point of Master Hand and possibly Crazy Hand, Event Matches set up scenarios with a specific context, and All-Star is a tense bout in defeating every playable character between rounds, now organized in series order instead of randomly like in Melee. A multitude of trophies is still curated in a menu, although the means of unlocking them take the form of a high-stakes minigame involving using the player’s accumulative total of coins as ammunition and shooting the trophies that appear on the board. Stickers act similarly to trophies as a catalog of Nintendo characters, but they are far less interesting. Target Test, Home-Run Contest, and Multi-Man Melee Brawl all return, but each is either a watered-down version of itself or adds nothing of value. Anything extra that Brawl adds to keep the player involved that wasn’t in Melee tends to be quite underwhelming. The Stage Maker feature sounds promising, but all it provides the player are the most rudimentary shapes and hazards possible. I bet Nintendo never figured that the player could still render a stage shaped entirely like a cock and balls with the little resources they gave them, which was bar none the most popular custom stage design. Masterpieces showcase a number of older Nintendo releases that involve the playable character’s past adventures, and it offers a solid selection of games. It seems cool while you’re in the moment until you realize that Nintendo isn’t going to give these games away for free, so they yank the player out of the demo faster than chewing gum loses its flavor. Why bother at that point?

All of these halfhearted modes that Brawl adds are fully compensated with one “extra mode” featured in Brawl that cements its legacy among its fellow Smash Bros. titles, and that’s the Adventure Mode, titled “The Subspace Emissary.” If I had to wager a guess, this colossal campaign was the reason why Brawl’s release date was frequently postponed. What was the amusing novelty of a crossover between Nintendo’s characters that shaped the identity of the series has transcended its place as a simplified fighting game into something of a cinematic, epic crusade with Nintendo’s characters at the helm.

It’s difficult to summarize the plot points of the Subspace Emissary’s story despite how grandiose a scale it sets itself on. This is mostly due to Nintendo’s characters persisting on the minimal yelps, cries, and squeals they all emit as opposed to spoken dialogue. Exposition throughout the whole campaign is expressed through mostly silent Peachisms (solving a skirmish with a cup of piping hot tea), Captain Falconisms (murdering a tribe of Pikmin in a flashy, cloddish manner), Warioisms (farting and picking his nose), etc. to further the plot. Still, I think I can detail the events eloquently enough to make sense of them. The villainous characters in Nintendo’s universe are executing a diabolical scheme to obliterate the world with an arsenal of black hole time bombs. Ganondorf and or Master Hand seem to be at the top of the excursions' villainous chain of command, overseeing the process from his dark domain. Meanwhile, other villains such as Bowser, King Dedede, and Wario are using a cannon whose arrow-shaped projectiles kill all of the Nintendo heroes that would stop their evil deeds, or at least immobilize them indefinitely into trophies and round them up. The first instance of this is when Meta Knight’s Battleship Halberd looms overheard and rains down the Plasmid grunts for Mario and Kirby to fight. A veiled figure called the Ancient Minister sets one bomb that engulfs the arena into a black void of nothing. Wario also uses the cannon on either Zelda or Peach as Kirby escapes with the one that survives. This conflict scene is essentially what occurs at each moment in the story, only with a different pairing of Nintendo characters (ie. Samus and Pikachu, Diddy Kong and Fox, Lucas and Pokemon Trainer, etc.) as all of the groups eventually rendezvous by circumstance. Also, each of the villains realizes how dumb this mission is and joins the rebellion. I can’t criticize the plot too harshly given the intrinsic flaws of a plot that involves all of these different characters interacting with each other. However, the sheer notion of all these characters interacting with each other in this context is also the campaign’s charm, even if it is fan service.

I love the Subspace Emissary or at least the overall execution of its gameplay. The 2D axis the series has always implemented for fighting translates into the beat em’ up/2D platformer as smoothly as slipping on a sock. Defeating the army of unique enemies never feels unnatural, but it does wear on the player after a while. The Subspace Emissary takes approximately ten hours to complete, and fighting the foes that the developers crafted for this campaign overstay their welcome after they halt progress to kick them into the dirt for the umpteenth time. Some call the Plasmids and their fellow allies in the evil army to be generic, but the large variety of them keeps their encounters relatively fresh. That being said, I’m not giving the same clemency to these levels. I’m not convinced that these levels all encompass a “Nintendoland” where all the characters reside. All the spirited and wondrous backdrops found across Nintendo’s library are subtracted into dull depictions that rely on the most base level of tropes to vaguely recreate something of a familiar Nintendo foreground. Even worse, the ending section, “The Great Maze,” is an amalgamation of every level that takes about half the length of the total campaign. It goes without saying that this section is a total slog.

Fortunately, a greater sense of inspiration in The Subspace Emissary is with its bosses. Unlike the unrecognizable legions of foot soldiers scattered around, most of the bosses will strike a sense of intimacy. Petey Piranha captures Peach and Zelda at the beginning, Porky (yes, his real cannon name) will bully Ness and Lucas in his spider mech, and Ridley will be fought twice in his normal form and his metal coat of armor from Metroid Prime. Is legendary Pokemon Rayquaza considered a “villain?” If not, the Loch Ness Monster Pokemon of the lake still makes for an engaging boss. I still like the bosses the developers made for the game because, like the others, they still offer a challenge with a diverse move set to learn and overcome. At the very end of the campaign, we learn that all the Nintendo villains were nothing but red herrings, and the vengeful God-Like being of Tabuu was pulling the proverbial strings. He displays his omnipotent might on everyone which makes him seem unbeatable. That is until Sonic the fucking Hedgehog pulls a Deus Ex Machina before he deals the final blow. I don’t care if this trope is contrived and stupid, this is the only way to introduce Sonic in his debut Smash title. Then, the player has to vanquish the malevolent force, and he’s no picnic. He’s a damage sponge with many unpredictable forms, one being a series of flashes that will kill the player on contact. Once he’s defeated, the land reverts to its normal state, signified by the shot of a shimmering sunset by a body of water.

We all need to stop pretending that Melee didn’t have any faults and that Brawl was a misguided sequel that couldn’t surpass “perfection.” Super Smash. Bros Brawl was a logical step in progress for a Smash Bros. sequel, and the mark of a successor in a series based on recounting the celebrated history of the most successful video game company of all time needs to up the ante. Nintendo’s attempts to craft a more casual experience by slightly altering the gameplay isn’t a big detractor (except for tripping. What the fuck were they thinking?) because it still reproduces the appeal of Smash Bros. However, Brawl might signal a point where it would’ve been wise to show restraint in the additions, and the more involved stages and lethal items should be subtracted the same as the clone characters were from the roster. As of now, Brawl is a unique outlier in the series because the ambitious Subspace Emissary campaign, or at least something of its caliber, wasn’t recreated for any of the future titles. As flawed as the campaign was, it still hits a zenith point of crossover potential that no other Smash game has recreated. Ideally, every subsequent Smash Bros. game is intended to be bigger and better than the previous ones but no matter how they augment future releases in terms of content, I will always return to Brawl, the black sheep of the series, for this reason.