(Originally published to Glitchwave on 10/20/2023)

[Image from glitchwave.com]

The Last of Us

Developer: Naughty Dog

Publisher: Sony Interactive Entertainment

Genre(s): Action Horror

Platforms: PS3

Release Date: June 14, 2013

Why does this so-called “masterpiece” that has received an outstanding flux of adulation over the past decade inspire such passionate feelings of rancor in me? Well, I don’t mean to come off like a snob (as usual), but I’m a gamer who likes playing video games. I’ve expressed my relative discontent with the seventh generation of gaming from roughly 2007-2013 countless times before, for it's an era synonymous with video games using their graphical and mechanical advancements to compete with the film industry. Many of the era-defining titles during this generation trimmed that dividing line between the two mediums to the point of hanging by a flimsy little thread of discernibility. It almost seemed like gaming was gallivanting around in film’s skin, reaping the praises the older visual medium was once and should ideally still be garnering until gaming shut film out of existence like a shapeshifting cosmic entity. The film industry theoretically shouldn’t worry about gaming’s growing ubiquity in the entertainment landscape, for both mediums satisfy two different artistic itches with their distinct meritorious strengths. However, upon seeing the success of The Last of Us and other games of its ilk that have achieved great praise for emulating the film’s cinematic properties, I wouldn’t blame the film industry for raising a concerned, suspicious eyebrow one bit. Sony subsidiary developer Naughty Dog, a studio whose previous works molded my love for the gaming medium (Jak and Daxter plus Crash Bandicoot to a lesser extent), redefined themselves as trailblazers in developing some of the generation’s most prestigious cinematic video games of that generation. Their Uncharted trilogy on the PS3 came first and was (unjustly) showered with high praise, but their 2013 game The Last of Us is a monolithic behemoth of laudation that transcends any and all credit given to any Uncharted title. My discrepancies pertaining to these cinematic video games are that they are like ordering a steak well done; it’s still the same delicious piece of meat, but all of the substantial flavor and fleshy texture has been sizzled to oblivion. Why not eat something else at that point? I don’t judge someone if they want to order their steak in this fashion, but grievances arise when the majority of people claim that well-done steaks are the best way to cook a cow knowing full well they’ve never bothered to try a bloodier strip out of the fear of contracting E. Coli and other food-related bacterial infections. What exacerbates my irritation is when the cultural mandarins feed off the sentiments of public opinion and meld the overrated title into the video game canon with the all-time greats that are more exemplary of the medium’s actual merits. Either that or the success of The Last of Us affirms my theory that mainstream video game journalists are nothing but glorified tech reviewers, approaching games like pieces of hardware and assessing them on their objective performance. My (hypothetical) Apple Watch should operate adequately as advertised, but no stronger emotions other than content satisfaction will resonate with me after I’m finished toying with it for the day, unlike a work of art. Actually, emotion is the crux of substance for The Last of Us, the facet of its cinematic performance that resonated with everyone who praised it and what surprisingly struck a chord with me once I gave The Last of Us a fighting chance.

At least The Last of Us knows what it’s doing from a cinematic standpoint, and this is evident from the game’s prologue. The events that promptly establish the conflict and tone for the duration of the game use an “adrenaline hook,” a term of my own creation defined by reeling the viewer into the story with high-stakes action and suspense. The atmosphere is content in the Joel Miller household located in the rural outskirts of Austin, Texas, where his adolescent daughter, Sarah, gifts him a watch for his birthday, and he banters with her on how she scrounged up enough money to afford it. This humdrum tranquility is forever upset when Sarah gets a call from her uncle Tommy, Joe’s younger brother, who panics over the phone as if the world is about to end. Little do these characters know, his frantic mood is actually a precedent for the duration of the game. Puffy spores from mutated Cordyceps plants have sprouted all over the nation, and the malicious effects of the airborne toxin they excrete have transformed a substantial percentage of the population into wild, inhuman monsters who scream and growl as they scratch and bite their victims in a savage frenzy. The infection will also spread to those who have sustained physical lacerations from one of the monsters, which means that the premise of The Last of Us is Zombie Movie 101. Joel’s process of getting the hell out of dodge with his brother and daughter goes awry due to the chaos ensuing from the zombie pandemic all around, so they are forced to escape the plague on foot. This slower method doesn’t work either as Joel is accosted by a military SWAT member on the charge against the outbreak, opening fire on Joel and Sarah on orders from a higher-up. Tommy subdues the soldier and Joel is unscathed, but Sarah is fatally shot and dies in Joel’s crestfallen arms. We’ve seen this zombie outbreak premise catalyzed in this way several times before, especially in the era of the cultural zombie craze when The Last of Us was released. Still, the pacing that coincides with the dichotomy of normal peace with the explosion of zombie pandemonium makes the tragedy that ensues an effective gut punch.

We do not witness how Joel grieves with the enormous loss of his only child, for the screen turns black and transports us twenty years later after that fateful night. Joel is only marginally greyer, but his demeanor along with the lengthy timespan that has passed suggests that he’s far more grizzled. A facet of The Last of Us’s zombie outbreak premise is the grim, irrevocable tone of such an epidemic. The state of the world has only gotten worse since it began two decades prior, and now it is in apocalyptic ruin. Buildings erected to serve as mankind’s architectural backbone are now ghosts of the society they were meant to support, and now they’re lofty equipment pieces of a dilapidated playground where the remaining humans play deadly games of hide and go seek for survival. The roads are fractured by gaping fault lines and finding a car whose battery and engine haven’t been frazzled to the point of no return is like finding a unicorn. The parasitic spores have crumbled society as drastically as a collapsed Jenga tower, and the damage done is impossible to amend. The untouched wilderness in every cityscape's background is beautiful, but the sight is ultimately bogged down by the urban decay in the foreground. It would be an awe-striking scene where one could bask in the still melancholy if not for the constant screeches of the infected and the whizzing bullets from the military. I usually chastise the visual murkiness in Triple-A titles of the seventh generation, but The Last of Us is one exception where a depressed tint is apropos to the depleted landscape.

The epidemic has vastly spread throughout the world over the two-decade period, and so has our protagonist Joel. This statement is affirmed by the fact that Joel now resides thirty hours away from his hometown of Austin to Boston, or at least the remnants of the New England metropolis as it’s just as destitute as anywhere else in the country. We have no idea how Joel has survived for twenty years or how he ended up on the opposite latitudinal end of the USA, but the conversations between him and a woman he’s affiliated with named Tess grant us some context of his current situation. Joel is now a smuggler who sneaks in contraband and a bunch of other elicit objects of interest past military-sanctioned lines to trade for even more risque rewards. Their rightful shipment of guns has not been properly transmitted to them for compensation, so Joel and Tess venture outward to get to the bottom of this mishap.

This early section with Tess is the game’s tutorial mode where the player should become acclimated to Joel’s gameplay mechanics, and one of them is crafting. Because the capitalist economy collapsed when the outbreak escalated by proxy, obtaining goods and services is no longer a one-stop shop convenience. Everything in this post-apocalyptic world is scant, which means that it is wise to conserve every resource that Joel scrounges up from off the ground. Ammunition for the various firearms in Joel’s arsenal is a given, but vacant households and former civic centers also have nifty tools strewn about that are essential to any emergency survival scenario. Despite the usefulness on their own merits, it’s the makeshift mingling of these items via the crafting menu that is going to prove vital to Joel’s well-being. For example, the combination of duct tape and one leg of a pair of scissors melds together to form a shiv, which can be used to force open locked doors and quickly dispatch an enemy from behind. Certain chemical properties of sugar mixed with packs of fertilizer combine to create smoke bombs, and Joel can stick a blade or two to that concoction which makes a deadly nail bomb. Alcohol, rags, and a strip of tape can craft Molotov cocktails, but those same materials are also needed to make medkits. Joel will occasionally find these to patch up his wounds on the field but does not rely on seeking them out and focusing on burning the scourge to a crisp in a glassy, fiery inferno. Materials for all of these tools are conspicuously found if the player even does a minimal amount of excavation off the beaten path, so Joel should never be unprepared to deal with the legions of enemies the apocalypse has created. It also helps that Joel comes about an eclectic smattering of firearms on his journey, ranging from the handgun and shotgun staples to a flamethrower and even a bow and arrow.

Of course, the amount of ammunition for any of Joel’s guns rarely surpasses single-digit quantities, so the wisest approach is to dispatch enemies by being sneaky. What I didn’t expect from The Last of Us was the emphasis on stealth and survival gameplay. Similarly to Uncharted, factions of enemies will be crowded around a relatively open space on the lookout for any undesirables, namely the protagonist. Obviously, these armed men will proceed to open fire on Joel if they catch a glimpse of him, and the game will then transition into a cover-based third-person shooter. Unlike Nathan Drake who exists in a Naughty Dog depiction of real-world modernity (albeit as a rambunctious action-adventure flick) where ammo is plentiful, the deprived Joel must make every bullet count, and the sparse amount of them is sometimes not enough firepower. This is probably because I set the game to “hard” difficulty after learning from playing four Uncharted games that Naughty Dog downscales the “normal” difficulty for noobs, but shooting a man between the eyes will somehow not stop him dead in his tracks. Therefore, using the element of surprise is paramount to survival. Years of evading the horrors of the post-apocalypse have sharpened Joel’s senses to the point of having sonar-like bat hearing, which is displayed as the player seeing silhouettes of enemies walking about while being obscured behind a wall. Using this to his advantage, Joel can tiptoe up to his target and either snap their necks in a sleeper hold or quickly stab them in the neck with a shiv like disposing of a prison snitch. It should be noted that humans and infected should be approached differently, as humans have a keener sense of sight while the infected rely mostly on sound. The creepy, ravenous “clickers” and the disgusting, apex-of-the-infection “bloaters” have been rendered completely blind by their advanced affliction, so Joel can quietly waltz past them and save his resources for more observant foes. It should also be noted that Joel is rather vulnerable when he’s in the spotlight of conflict because his aim with any gun is shakier than a blender and he reloads his gun like old people fuck. On the spectrum of the survival horror protagonist, from the kickass boulder punchers from Resident Evil to the hapless schmucks from Silent Hill, Joel ranks somewhere in the middle. Because Joel’s battle prowess is confined by inherently human capabilities, it’s best to put some consideration to any conflict.

For the rinse-and-repeat nature of the enemy encounters, they are all refreshing juxtaposed with the other gameplay mechanics on the field. I’m not implying that the repetitive combat becomes invigorating once again after a prolonged break, but only because traveling across the shattered American plains is mind-numbing. Without the breaks of action in between, I’d definitively umbrella The Last of Us in the category of “walking simulator” because that's a clear estimation of the gameplay. The Last of Us forgoes the parkour platforming found in Uncharted, for Joel is an emaciated middle-aged man with crippling joint pains. Puzzles are also omitted because they wouldn’t fit the rationale of the once-bustling city streets as opposed to encountering these thinking challenges while spelunking in the arcane crypts as Nathan Drake. Occasionally, Joel will need to cross a gap or reach a high ledge which requires some semblance of thought to proceed, but it simply boils down to grabbing a nearby ladder or a portable dumpster as a solution to every obstacle. Sounds riveting, doesn’t it? Truthfully, if these sections required any more effort from the player, the game would probably risk alienating the broad audience it desperately wants to cater to. However, I still fail to understand why anyone, experienced with video games or not, would be enthralled by gameplay so effortlessly simplistic. For a gamer, it’s naturally equivalent to watching grass grow but even for someone who doesn’t normally play video games who ideally wouldn’t be turned off by the simplicity, why wouldn’t they just watch a film? Why would they seek an alternative visual medium if the differences are only minimal? Is the notion of an interactive film really that novel? The Last of Us skates by offering only the absolute bare essentials of gameplay mechanics, and it’s the source of my core discrepancy with the game’s overwhelming glory. One could argue that the hiking trail that is The Last of Us’s gameplay is intentionally serene and the player is intended to immerse themselves in the tranquility but if this were the case, why would the game constantly interrupt that stillness with barrages of monsters and military men? Naughty Dog has shaved the gameplay beard down to total nakedness, and the stubbles it has left behind hardly constitute facial hair.

Actually, I have a definitive explanation as to why The Last of Us gets away with its facile gameplay mechanics, and the reason is why I came to tolerate a game where all I was accomplishing was pressing the analog stick upward with little instances of deviation. While I was moving Joel around the American wasteland, what kept me from utter boredom was the character interactions that were progressing The Last of Us’s narrative. My precognition on The Last of Us’s mechanics was affirmed to be correct, but what I didn’t count on was being enraptured by the story that the gameplay was flimsily supporting. With this, I understood the appeal of The Last of Us and why it is widely commended.

The overarching task assigned to Joe on the streets of Boston is to trade a special package to the Firefly resistance group for the misplaced shipment of guns. What is this vital piece of contraband? A fourteen-year-old girl named Ellie, who is well acquainted with Marlene, the commander in chief of the bug-themed militia Joel and Tess are trying to appease. What is so special about this adolescent girl? Well, she’s been bitten by an infected and hasn’t succumbed to the damning effects usually associated with spreading a biological scourge and only sustains a ghastly rash on her right arm. Marlene believes that her incredible immunity is the key to discovering a vaccine for the virus, so it is of great importance that Joel escorts her to the headquarters of her group unscathed to research her and conduct surgery if needed. The only problem is that the Firefly’s place of operations is at least two time zones away from Boston, so Joel must acclimatize himself to having a teenage girl in close proximity to him for two thousand miles, traveling mostly on foot. Do not fret, for Marlene dumping Ellie off on Joel is not an instance of the game pulling the comfortable wool rug out from under the player, igniting a harrowing escort mission like the second half of Silent Hill 4. Ellie was born into societal devastation and madness, so she’s perfectly accustomed to dealing with the products of the plague despite her age. She’s invulnerable to all enemy fire and feral zombie gnashing, and even chips in with giving Joel items and ammunition from time to time.

While Ellie does not annoy or inconvenience the player at any point, the same cannot be said for Joel. He’s not all that enthralled by the prospect of delivering this girl to the other side of the country via a process that’s slower than snail mail, as one could reasonably imagine. Given that he’s an all-American, red-blooded male cut from the same masculine cloth as Ron Swanson and she’s a vulgar and excitable young lady who is young enough to be his daughter and then some, their personalities don’t quite mesh. However, this dichotomy between them is the basis of their chemistry as characters. Joel is as stern with Ellie as he would be with Sarah in this situation, although it’s difficult to say whether or not Sarah would’ve been as defiant with Joel’s wishes and demands as Ellie is. One altercation between them gets so heated that Joel has to explicitly state that Ellie is not his daughter, alarming the player into thinking that Joel would commit a heinous act against Ellie as opposed to a young girl he has an unconditional love for. When they bicker, the dramatic tension is palpable, but it just makes the lighthearted moments between them like driving out of Boston in a car obtained from the insufferably churlish smuggler Bill and Ellie curiously asking Joel about the times before the epidemic all the sweeter. They’ve got a long way to go together, so they’ve got to get along at some points to survive not only the hazards of the fallout but each other as well. Also, the voice actors deliver Joel and Ellie’s lines fabulously.

Eventually, as one would anticipate from Joel and Ellie’s relationship dynamic, she starts becoming his surrogate Sarah. After the aforementioned tense pivotal scene, Joel ultimately doesn’t dump Ellie off as his brother Tommy’s responsibility and decides to finish what he started. Once he makes this decision, his rapport with Ellie improves as she no longer is treated like an annoying burden. While their relationship has delightfully improved, Joel getting impaled on a piece of fallen railing after a scuffle on the campus of the fictional University of Eastern Colorado seems like a turning point where Joel has been prematurely erased from the Ellie escapade equation. This change seems dreadfully concrete when the “Winter” chapter begins and Ellie is hunting for food in a snowy lakeshore forest by herself. During this task, she comes across two scavengers named David and James and fights off a hoard of infected with the former of the two men. While David initially seems friendly like he’s going to jump in Joel’s shoes as Ellie’s protector, he starts antagonizing Ellie once he reveals himself to be the leader of the group that attacked her and Joel at the university and he’s out for retribution against them. His group is also cannibals, which heightens the suspense that Ellie is in grave danger. Fortunately for Ellie and the narrative, Joel is resting his stitched wounds on a mattress on the cold basement floor of a safe house. Even though his condition is bad, the notion that Ellie is in danger prompts him to spring into action in the frigid haze of a Colorado winter with David’s rabid cannibal goons everywhere. Like George Romero’s Day of the Dead, The Last of Us implies that in a hectic world full of monsters, humans are still the most monstrous creatures of all, conveyed through Ellie’s diner duel with David where he’s shed the polite facade and has fully embraced his true maniacal, sadistic nature. When Joel reconvenes with Ellie after she is traumatized by what she just experienced with David, he wraps his arms around her like a big cuddly bear and calls her “baby girl.” It was at that moment when Ellie was no longer being taken care of by Joel out of obligation but by pure affection. The end of this hair-raising chapter was when I became totally invested in the characters and their story.

The “humans are bastards” theme is but a slight motif across The Last of Us. The game’s core theme that I have deduced is preservation in dire circumstances and how it conflicts with the greater good. Throughout the game, many human characters have had to sacrifice what they cherish even if the result is soul-crushing. Tess, Joel’s original partner, doesn’t want to reveal her new infection and only does when Ellie exposes her. As a result, she lets herself get gunned down by the pursuing military before the infection takes over her brain. The African-American brother duo of Henry and Sam who partner up with Joel and Ellie when they’re stranded in Pittsburgh share a bond tighter than knotted rope. Yet, when Sam is infected and starts attacking Ellie, Henry shoots his little brother square in the head, devastatingly killing himself immediately afterward not being able to cope with what he had to do. But the point is, he still did it because he knew it was the correct course of action. It seems like the only way to prevent oneself from being a bastard in times of zero hope is to improve the future which boosts humanity’s morale. This is a moment of clarity that every moral character in The Last of Us eventually comes to. One would expect Joel to follow this altruistic pattern considering he’s the game’s protagonist, right? After finally locating the Fireflies in Salt Lake City and embracing his father-daughter dynamic with Ellie, Joel is an eager beaver prepared to finish the mission and spend his days spending time with Ellie in his brother’s fortress in Wyoming. His twenty-year trauma which he thinks has been healed through Ellie is dreadfully tested when he learns that Ellie’s operation to create that vaccine will kill her. Unable to bear the pain of losing her like he lost Sarah, he breaks through the facility's defenses and carries an unconscious Ellie out of the operating room, paralleling the opening sequence with Sarah. Marlene tells Joel that dying for a noble cause would be Ellie’s wish, and she’s not bullshitting him. Still, Joel fully knows this and murders her for getting in the way of his wishes. With an awakened Ellie expressing feelings of unease about not going through with her destiny, Joel feeds her a line of lies to assuage her concerns, even if it’s really just gaslighting for his own benefit. The fact that this was Joel’s decision is not surprising. He’s been through twenty years of hell, and it all started when he lost the most important person in his life at the very start of it. He even gets the impression that trauma is a dick-measuring contest where nothing anyone else has experienced in a barren world defined by loss even compared to what he was forced to endure. What is surprising is how the narrative has made us all disgusted and ashamed of the man whom we’ve been rooting for the entire game, almost shifting into the game’s core antagonist for committing the most deleterious act of self-preservation. Yet, while taking the honestly sorrowful events of his past into consideration, he’s still a sympathetic character, albeit garnering pity rather than genuine sympathy. I was appalled.

If I am to be so bold, I declare that The Last of Us is the ultimate Uncle Tom in gaming. The Last of Us sheds a sizable chunk of its innate video game makeup to please the so-called high arbiters of art, embarrassed at how it will be perceived by them if it flaunts its true nature. Because The Last of Us goes down smoother than strawberry yogurt, it gets a pass from the snooty cultural elite as “one of the good ones.” It gets the privilege of being compared to Hollywood films, but they will never accept it as one of their kind no matter how hard it tries. How do I know this? One of the various kernels of The Last of Us’s success is a television series, a faithful adaptation of its video game source material. Google the title of the game and you’ll get nothing but the TV show until the fifth or sixth result, even though it aired the year I’m writing this review and the game is a decade old at the point. Isn’t this further proof of how attempting to fraternize with film as a “degenerate” piece of media is only doing harm to gaming instead of helping it reach a standard of mass acceptance? Considering how the gameplay of The Last of Us is shallow and tedious, perhaps the exquisite story it presents is better off as a TV series. Still, there are video games that achieve strides in artistic innovation that are far more deserving of a patron saint status for the medium even if they aren’t as well-known by the public, even some of The Last of Us’s seventh-generation contemporaries. After what I’ve said, I still can’t believe that I’m curious to see what unfolds in the sequel. Perhaps I’ll watch someone play it on the internet instead of experiencing it firsthand, kind of like a television show.

(Originally published to Glitchwave on 11/7/2023)

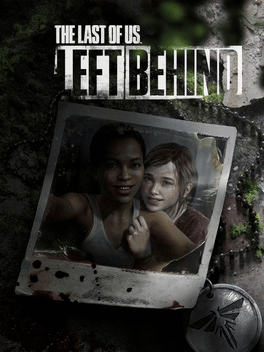

The Last of Us: Left Behind

Category: DLC

Release Date: February 14, 2014

Ellie controls the same way she did the base game here in her solo DLC campaign. She’s physically weaker than Joel in both offense and defense on account of her being an adolescent girl who is still growing (but is probably devastatingly malnourished). However, she compensates for her lack of strength with her youthful scrappiness, making the stealth sections easier by simply plunging a blade into her enemies quickly as opposed to the struggle of snapping their necks that Joel performs. Left Behind features zero new weapons, so the player should already be an Ellie expert for their time playing as her in the main game. I argue that the developers should’ve introduced at least one new tool to use against the hostile elements that exist around them, but perhaps it would’ve been nonsensical for Ellie to find a new contraption just to abandon it when the DLC circles back around to the events of the base game.

Left Behind alternates between the relatively recent past before Joel met Ellie and the present predicament of finding Joel medical supplies so he doesn’t bleed out on the cold mattress he’s lying on and leave Ellie on her lonesome. The relevance between the two periods of Ellie’s life is that the past section highlights the last moments she spent with her dear friend (and potential lover) Riley. Riley is summoned by Fireflies leader Marlene to join her on a mission elsewhere outside of the Boston area, so she treats Ellie to one last hurrah of fun in an abandoned shopping mall before she parts to serve the resistance. Either that, or the joyous atmosphere she’s creating for her and Ellie is an attempt to make Ellie beg her to stay so she’ll have a reason not to leave. Using their imagination to reignite the neon sparkle spectacle of a pre-apocalypse shopping mall, the girls have a grand ol’ time together. That is, until they accidentally provoke a horde of infected by playing some music a little too loudly, resulting in both of them getting bit and waiting out the inevitable like MacReady and Childs in the Antarctic. While Left Behind doesn’t add any weapons or tools, the lighthearted gameplay mechanics used during the various sections with the squirt gun battle and Ellie revisioning a boss battle in a defunct arcade fighter with the button combinations are fairly fresh and enjoyable.

Riley being bitten by an infected person is not a shocking gut punch of a conclusion, but that is not the intention. Ellie has mentioned that Riley was one of her fallen comrades at the end of the base game, so those who are crushed by Left Behind’s ending were not paying attention. The purpose that the contrasting sequences have is to showcase that Ellie hurts as much from the effects of the spore infection as Joel does and that she is as afraid of losing him as he is her. The girl’s camaraderie in the most mirthful moments The Last of Us offers is actually infectious, putting the hidden beauty of the apocalypse into a perspective that was not apparent in the base game. We jump back and forth from these cherished memories to times of trouble not only to present a dichotomy between the pleasant past and the perilous present, but how Ellie desperately does not want to endure the tragic pain of losing someone close to her again and is emotionally prepared for the worst case scenario because of it. It makes us respect her decision at the end of the base game even more and resent Joel at the same level for his.

Like the base game it stems from, The Last of Us: Left Behind succeeds on its narrative strengths while neglecting the gameplay. All it offers is character development for the deuteragonist by letting us become privy to her tragic struggles we’re already aware of and not much else. The few quirky moments in the mall slightly mix in some unfamiliar elements, but the game treats these sections as flippantly as the girls do by flatlining the stakes of them. Considering this DLC did not come as a free extension at its initial PS3 release, I’d feel ripped off if I paid for this paltry piece of content (I have the remastered version on the PS4 where Left Behind is included for free). I guess the conclusion is to simply watch all content involving The Last of Us for its full effect. Hey, it seems like what Naughty Dog wants.

No comments:

Post a Comment