(Originally published to Glitchwave on 5/1/2022)

[Image from glitchwave.com]

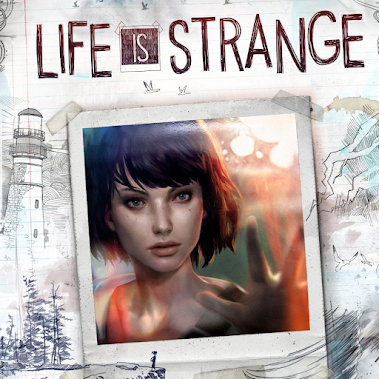

Life Is Strange

Developer: DON'T NOD/Feral Interactive

Publisher: Square Enix/Feral Interactive

Genre(s): Graphic Adventue

Platforms: PS3, Xbox 360, PC, Xbox One, PS4

Release Date: January 30, 2015

Liking things ironically has more merit than being a stodgy hipster or fitting in with the absurd, existential humor of the millennial/zoomer generation. Some media pieces genuinely blur that line between pure enjoyment and being an unintentionally ironic farce. One could argue against something with this specific appeal because of the glaring issues it would fundamentally have, thus negating any of its allure on an objective scale. However, there is something truly marvelous about artistic works with this kind of appeal. How else do you explain why Ed Wood still has a relevant legacy despite his consistently bad filmography? Tommy Wiseau’s The Room is just as revered as any Oscar-worthy film released the same year, albeit for drastically different reasons. Certainly, bad video games can also inspire the same sort of derisive joy as any other medium. One can appreciate the absurdity of something like Shaq Fu or cackle at the broken mess that is Sonic 06. They say that the opposite of love isn’t hated, but rather it’s apathy, and this notion definitely pertains to the glibness of liking objectively bad works of art and entertainment.

Life is Strange is one of these games that I love to hate. Its fans would be appalled at the comparisons I’ve made to some of the most notably bad games to ever exist, but Life is Strange exudes this same quality for me. That being said, Life is Strange is not one of the worst games of all time. It has plenty of objectively good qualities that keep it from swimming in the same abysmal cesspool of disgust and derision as the aforementioned titles. The game has even received plenty of accolades from several gaming outlets. However, Life is Strange is no masterwork. Life is Strange still achieves this sensation of ironic pleasure through means other than mechanical incompetency. Over the past few decades, video games have reached a point of evolution where they now have cinematic elements. Some modern video games give precedence to these newfound cinematic elements to the extent that they seem like interactive movies instead of video games. Because of this, gaming has reached a point where the greater emphasis on cinematics can offer the same unintentionally humorous qualities that come from substandard films. These elements range from bad characters, dialogue, and story writing, and Life is Strange has all of this in spades.

I vaguely heard promising things about Life is Strange from various sources on the internet and saw that it was free to play on the XBLA marketplace. I did not read the fine print, however, and discovered that only the first episode of this game was free to play, and it would cost me a pretty penny or two to finish the Life is Strange experience. I have my own hangups about episodic gaming because I don’t trust the industry. Developers/publishers might use the episodic format to exploit a loophole of what is considered a finished project. They tend to treat individual episodes as full experiences rather than the parts of a whole one, giving them the convenient opportunity to jump ship whenever possible and leave the consumer with an unresolved product. It’s like getting free samples of a food product and finding that what you’ve been eating isn’t available as a full meal. See Half Life 2 and its episodic cliffhanger that Valve never bothered to resolve. Fortunately, Life is Strange was complete and divided into five episodes by the time I played it, relieving me of my fear of being blue-balled by a video game company once again. Now I realize that offering the full first episode of Life is Strange as a sample to purchase the whole game was an ideal circumstance. If I didn’t care for the first episode, I would’ve simply saved my money and not bothered. Given what I’ve said about Life is Strange’s poor quality, why did I buy into this bullshit? Initially, there were plenty of elements to Life is Strange that intrigued me to keep playing.

I’m ashamed to admit this, but Life is Strange introduced me to the graphic adventure genre. The genre’s golden age defined by the quirky works of LucasArts was before my time, and the subsequent works of their successor Telltale were completely alien to me when I was playing video games as a kid. I first played Life is Strange at the age of 21 when I was open to playing a game in a genre where the gameplay consisted of walking around finding clues to puzzles with the occasional NPC conversation. As an entry to the graphic adventure genre, Life is Strange rips its foundation straight from the book of TellTale. Its 3D graphics and textures are heavily stylized, options in conversation make up a sizable portion of the gameplay, and the game’s progression is somewhat determined by the player's choices. It’s the industry standard for the modern graphic adventure game, and Life is Strange at least adequately emulates its influences in terms of gameplay. One aspect that is comparatively lackluster to the TellTale games is the visuals. The graphics themselves are appealing as there is a warm sheen to them that helps convey an intentionally ethereal tone. However, the character models move much more rigidly than the characters in any TellTale game. Dontnod, the developers of Life is Strange, were backed by Square Enix on this project, one of the most notable triple-A companies in the industry. There is no excuse why Life is Strange shouldn’t be up to par with the fluid character animations of TellTale. Life is Strange is supposed to exude the atmosphere of an indie, “mumblecore” film, not the budget of one.

The unique gameplay mechanic that separates Life is Strange from its graphic adventure contemporaries is the time loop gameplay mechanic. Max, the protagonist of Life is Strange, can warp back to a certain period. In doing this, she alters the chain of events while being the only person who remembers what had occurred. Her ability is a ripple-effect proof memory trope seen in plenty of science-fiction media. It’s also the mechanic that suckered me into Life is Strange. I am fascinated with any time-travel-related fiction and its intriguing tendency to subvert rational physics for narrative. Max is spontaneously granted these powers without any explanation like Gregor Samsa, so her power’s role in the narrative is simply a plot convenience. Questioning the genesis of Max’s powers will only cause unnecessary confusion for the player. When taking her powers at face value in terms of gameplay, this mechanic is Life is Strange’s killer app. Max can rewind time on most occasions under a certain time constraint, represented by a winding spiral in the top left corner of the screen. The player can use the move at any point but will often be utilized to solve puzzles and to indecisively change their responses in the interactive dialogue portions. The time mechanic makes the puzzles more interesting and involved, especially when the game imparts fetch quests to the player. Puzzles that incorporate the time-bending technique are fairly engaging as they tend to involve multiple steps like dumping paint on Victoria and saving Chloe from being decimated by an oncoming train. These puzzles can be tactfully executed without deviating from the already finicky rules associated with fictional time travel. Using the mechanic during dialogue options allows the player to pick the best option, implementing a trial and error option to the game.

Life is Strange also makes the wise decision to entice the player initially by starting the game with a crucial scene. The episodic format of Life is Strange gives it the pacing of a miniseries on television. If there is something that separates television from film, it’s the more accommodating pacing involved with telling a story in most television series. Television audiences have lower attention spans than most people, or at least that’s what executives will have you believe. The bursts of exposition confined to a certain time frame allow television to offer quicker payoffs as opposed to the slow burn pacing seen in films. The opening sequence of Life is Strange is what we in the industry (really meaning me) call an “adrenaline hook”. This phrase refers to opening with a high-stakes scene without any context, which then makes the audience intrigued and want to fill in the gaps, like the very opening scene of Breaking Bad. Max finds herself in a wicked storm on a cliffside hill near a lighthouse. The ominous cyclone in the water lifts a boat out of the water, and Max is crushed by the debris that falls from the lighthouse. She wakes up in a cold sweat in her photography classroom while class is being instructed in frenzied disbelief that what she just experienced was merely a dream. While this scene is given more context later on and serves as an effective opener, this isn’t the contextless opening scene I was referring to. Life is Strange continues to hook the audience with arguably the most pivotal scene in the game. Max runs to the bathroom after her dreadful nightmare as two teenagers of different genders run in arguing about something unbeknownst to them that Max is in there listening to them. The argument gets so heated that the boy pulls out a gun and shoots the girl, leaving her mortally wounded on the bathroom floor. Max realizes she can use her powers to prevent this from happening as she rewinds time and pulls the fire alarm to prevent the fatality. One harrowing scene follows another to alarming peril, and the player feels as tense and frazzled as Max, hooking them into the plot to put the pieces of what they just witnessed together.

With all of the positives, I’ve stated about Life is Strange, why does this game inspire mixed feelings of both awe and contempt, causing a facetious reaction as a result? Well, all of the positive aspects that Life is Strange introduces as early as the first few scenes ultimately crumble upon themselves, both when the context to the ambiguity is resolved and when the narrative ruins all of the gameplay elements. The core problem with Life is Strange that makes so many elements faulty and gives it an unintentionally funny appeal is its creative direction and the intended ethos. The game was made in the mid-2010s and is set around that time. One of the most prominent cultural mainstays of that time was the prevailing “hipster” trend among twenty/thiry-something-aged millennials. This culture was spurred by many internet outlets. It was defined by trends such as introspective, sensitive indie music, pseudo-intellectual savants, being politically savvy, and having a cynical, almost nihilistic disposition on life. Life is Strange is overwrought with all of these characteristics to a hilariously transparent degree. The game is set in the fictional town of Arcadia Bay, Oregon, a pacific northwest town near the hipster capital of America. Blackwell Academy, the school that Max attends, is a private liberal arts boarding school. Even the douchiest of dudebro jocks here would get in a tizzy over a rape joke. Being that the characters are the same age as me and that I went to a liberal arts college, I am more than familiar with characters like these and have a history of being irritated by their smug auras and general self-righteousness. Does this mean that I have a negative bias against Life is Strange because it conjures up unpleasant memories of being yelled at by girls with short pink hair and piercings about how I’m not allowed to like the movie Ladybird because “women need more representation in films without men adulterating it with their sexist gaze (true story by the way)?” In a way, yes, but I’m not the only detractor of Life is Strange because of this. However, the magic of Life is Strange is that it feels as if this game was made for millennials but not made by millennials. I have a feeling due to all of the unintentionally humorous elements in this game that these writers attempted to capture the youthful experience of disenfranchised youth but came up short with their intent.

One of the more ubiquitous elements that make Life is Strange unintentionally hilarious is the dialogue. I don’t know how the dialogue in Life is Strange couldn’t have been hilariously bad. A group of middle-aged Frenchmen in business casual attire sitting at a round table trying to write like a modern American teenager couldn't have been anything less than a total disaster. While the situation in the introduction is tense, the dialogue between Chloe and Nathan, from the get-go, is rife with malapropisms and awkward “hip” lingo. Chloe’s first line of dialogue refers to her maligned step-dad as “step-ass” and says she wants to talk “bidness”. Later in the game, Nathan tells Max to fuck off by saying, “get off my crack, whore”. A favorite of mine that split my sides is during a school party when one inebriated student says he just “ripped some dank OG bud.” If this game resonated with more millennials as intended, Chloe’s trademark “hella” would have stormed the 2010’s lexicon of vernacular. Oh, and how can we forget Max saying, “ready for the mosh pit, shaka brah?” Is there any need to further explain why these snippets of dialogue can cause nothing but laughter? These lines aren’t spoken by one specific character but the entire cast of teenagers. For better or for worse, this is what older generations think me and my generation speak. In some cases, they aren’t that off the mark. I feel as if slang is more prevalent across the speech of my generation than that of previous ones, but the issue is that it’s too gratuitous here. The characters talk like this even in the most hectic and dire situations, seemingly unfitting for the scenario. It’s almost as if older generations think younger people are ineloquent to a fault, something I certainly take offense to. As for the voice acting, I suppose the actors did their best with the material and direction they were given.

I can almost forgive the haphazardly hip dialogue in Life is Strange only if the characters weren’t also rife with glaring flaws. Max Caulfield is an unassuming young woman with many typical protagonist traits. She’s demure, soft-spoken, constantly has a doleful facial expression, and her wobbly tone sounds like she could turn on the waterworks at any moment. She logs her feelings in a journal daily, she wears modest clothing, and the main focus in her photography class is taking artistic selfies. She’s Dontnod’s depiction of the modern teenage girl, but there is another element of her role as a protagonist that irks me. Caulfield, her last name, is no coincidence. It directly references Holden Caulfield, the protagonist of JD Salinger’s brooding young adult classic, “The Catcher in the Rye.” Max even has a poster of the book’s cover with a legally sanctioned title to make this connection even more overt. The brooding, cynical correlations are fairly clear, but not to the same extent. Holden Caulfield was an inherently unlikeable protagonist whose detailed angst emitted his myriad of flaws. In Life is Strange, the writers want the player to think that Max is a redeemable protagonist by having her be the Blackwell Academy collective’s de facto therapist. She comes to the aid of every Blackwell student to solve their problems, whether it be keeping their pregnancy scandal under wraps or taking a girl out of suicide. The writers did this to make the player feel like she is a kind, considerate person. Still, I feel this contradicts Max’s other characteristics stemming from Holden Caulfield’s general misanthropy. The game should let the player decide whether or not Maxine shall treat her peers with compassion or scorn them, but it’s another way to expose the fact that choice in this game doesn’t really matter. Overall, Max’s intentionally quirky traits that are supposed to make her likable come across as brooding and wince-inducing.

Max’s questionably effective individual role as a protagonist does not compare to the enraging, blood-boiling relationship she has with the game’s deuteragonist. It turns out that the girl whose life Max saves in the bathroom is Chloe, her former best friend who she hasn’t seen in years after moving away during their formative adolescent years. They reconvene after the events earlier that day, and Max finds that Chloe has changed quite a bit since they were thirteen. Chloe is now a rambunctious punk who dropped out of Blackwell and sticks her middle finger up at the world, screaming “fuck you” at everyone she sees, most notably her Blackwell security guard stepfather David. Personally, I find her punk persona laughable. She vaguely has the punk-rock attitude but then her “punk” playlist consists of Bright Eyes and Sparklehorse? Are hardcore kids freebasing heroin to The Smiths these days? Again, this is what middle-aged Frenchmen think punk and their culture is, but that is a nitpick that barely scratches the surface of the problematic character that is Chloe Price. I could write an entire essay about how unlikeable, vexatious, and utterly insufferable Chloe is, but other critics of this game have already beaten me to the punch. How about a highlight reel? Chloe is absolutely irresponsible and ungrateful, leeching off her poor parents while also screaming obscenities at them. She is impulsive to the extent that it seems like she believes her actions are inconsequential. An altercation with her drug dealer Frank leads to her killing him and his dog with a gun she waves around like a toy. She’s preposterously selfish and unsympathetic. When Kate Marsh either kills herself or attempts to kill herself, depending on the player’s actions, she couldn’t care less as she continues to bellyache about her problems. She’d even steal the money from a handicap fund to extenuate her debt to Frank. All the while, we’re intended to believe that Max and Chloe are the best of friends and this reunion reinvigorates their long-lost friendship. However, Chloe uses Max and her powers as nothing but a tool for her self-interest and throws a tantrum wherever Max expresses any concern or objection to Chloe’s ideas. Sounds like a wonderful pair, don’t they?

The main reason for Chloe’s dissent into absolute moral depravity is the trauma of losing her dad in a car accident when she was thirteen. Max then discovers that one of her powers is warping to a time and location seen in a photograph. She does this with a photo taken that day and prevents the accident from happening. If anyone is familiar with fictional time-travel rules, the butterfly effect occurs, and the course of history is altered. Max is now one of the popular, preppy girls at Blackwell, sitting in the ranks of her once rival Victoria Chase. Chloe is still not a student in this fabricated future, and Max goes to her house to find that she is a wheelchair-bound paraplegic due to another car crash only in this timeline. Here, Chloe is anything but the one we’ve come to know and not love due to being dealt a radically different set of circumstances. Here, Max and Chloe rekindle a believably sweet and substantial relationship until Chloe has Max enact assisted suicide to alleviate her pain. Surprisingly, the death of a character is almost poignant, except that Max treats this reality as a simulation and travels back to the realm of familiarity where Chloe is a raging thundercunt. She’s relieved to see Chloe with working legs, but the player is anything but glad to see her. The writers had to make Chloe a borderline vegetable who is euthanized to elicit any kind of sympathy for her and make everyone not hate her guts. Does any other sensible person here also find this to be a huge problem?

Other Blackwell students are relatively unique, but many are inconsequential to the plot. There’s the pudgy victim of circumstance Alyssa, stoner Justin, resident hot chick Dana, fat school punching bag nerd Daniel, etc. Their frequent occurrences make the school feel lived in, but they are ultimately relegated to the background. Max’s friend Warren is a notable character without any sway but still has some major precedence due to his embarrassing simping for Max. The (attempted) suicide of timid, good-natured Christian girl Kate Marsh is a massive plot point, but no matter the outcome, she ultimately sits on the same bench in the background of Blackwell, or so to speak. I wish she appeared more after her incident because her predicament is much more sympathetic than Chloe’s ever was. The staff of Blackwell shares the same role as the students, with a few exceptions. Mr. Jefferson is Max’s dashing, world-renowned photography teacher who has a dominating presence to the point where it feels like he’s the only teacher at this school. David, the security guard and Chloe’s “step-ass,” has a negative dominating presence where we are supposed to believe he’s the villain. Considering most of his contention is with Chloe, David’s anger is understandable. Then there are Nathan Prescott and Victoria Chase, the clear antagonists of Life is Strange that the players intend to root against. However, the game makes it a little TOO clear that we’re not supposed to like these preppy Vortex Club members, the “phonies” in Max’s world, by making them so malevolent that it comes off as cartoonish. It’s hard to figure out how these two people have organic relationships and can function in society.

The plot of Life is Strange that holds all these banal and/or knotty characters is probably the biggest detriment overall. The hook that drives the player’s interest early in the game progressively gets weighed down by forced plot conveniences. Most of the time Max and Chloe spend with each other is solving the mystery of Rachel Amber, a pretty and popular girl from Blackwell who was Chloe’s best friend in the wake of Max’s absence. Her disappearance correlates with an incident involving Kate Marsh, where Nathan Prescott drugged her at a party and recorded her acting foolish in an intoxicated stupor. The blowback she gets from her peers and her friends once this video goes viral escalates to Kate jumping off the roof to kill herself, or attempting to, depending on if Max gives her the right responses. Either or, there is something fishy in Blackwell, and the two “best friends” must get to the bottom of it.

Meanwhile, the storm Max envisioned in her dream is a looming threat that might occur and potentially wipe out the town. The duo finds disturbing photos of Rachel and Kate drugged together, which affirms their suspicions. They lead this to a creepy studio in a barn with binders on binders of passed-out girls and find that Rachel has unfortunately passed away. The plot offers the player a mess of red herrings ranging from David, Frank, Nathan, etc., but none are substantial leads. It’s revealed that the perpetrator is Mr. Jefferson, who kills Chloe and anesthetizes Max. Mr. Jefferson being the killer was shocking to many, including myself, but I realize that’s only because this reveal doesn’t make sense. What is Mr. Jefferson’s motivation? We don’t know because he doesn’t say it, and the player can’t make sense of it through context clues. It’s also unclear exactly what he’s doing when he drugs these girls. He’s taking pictures of them passed out in his studio bunker, but one would think there would be sexual connotations with these actions. Rachel died from an accidental overdose, so there’s no murderous intent either. Is it a case of the writers being censored or thinking these motives were too gruesome? The game is intended for mature audiences! Mr. Jefferson’s role as the antagonist is confusing as a result.

The final chapter is when the plot implodes on itself to the point of a nonsensical clusterfuck. Max finds herself in Mr. Jefferson’s lair and saves herself by warping to the scene of the selfie she took in his class on the first day. She tells David about Mr. Jefferson and Nathan and they get their comeuppance. In this alternate reality, Max’s artistic selfies are being lauded at a San Francisco galleria. It seems like the ideal timeline, but that monster storm will still blow through Arcadia Bay and wipe out the town. Through a confusing Silent Hill-esque surrealistic nightmare sequence, Max realizes that the only way to prevent the storm is to return to the time before she used her powers. She also realizes that preventing the storm also means that Chloe dies.

The player should know by now that the disclaimer at the beginning was a flat-out lie and player choice doesn’t mean shit, but the ending choice the player has to make for Max is hilarious and a kick in the teeth. Let’s see: save the moody, selfish, despicable blue-haired uberbitch who uses Max as a tool or save all of the innocent people who don’t deserve to die…it’s such a hard choice! Besides, the developers provide some fanservice with Max kissing Chloe goodbye with some tongue action! Yipee! This decision takes Max back to the bathroom on that fateful day. Chloe dies, but it turns out that Nathan and Jefferson were arrested anyhow, and there is a funeral service for Chloe. This is by far the best timeline that Max wished to come to, and anyone who says otherwise is full of shit. I’m convinced that the other ending where Max and Chloe drive through the town's wreckage (how the hell did they survive!?) is seen by people who are on their second playthrough and choose it out of curiosity. From the former choice, I anticipated the same feeling I got from the ending of Majora’s Mask, but all of Life is Strange turned out to be all for not anyways. Max did not need to cause several alternate timelines to build the strength to conquer an enemy; in fact, she didn’t even need to use her powers at all, and things would’ve been hunky dory. All of this negates the entire story.

For the most part, Life is Strange is a competent game that functions well as a graphic adventure title. The time loop mechanic is used well in the gameplay and makes it more accessible for those unfamiliar with the graphic adventure genre like I was when I first played it. However, the most vital aspect of a graphic adventure game is not the frills of the special mechanics. The story and characters drive the quality of a graphic adventure game, and Life is Strange fails in this department to an embarrassing degree. This team of Frenchmen attempted to make a profound work of art delved into relevant teenage subjects like alienation, abuse, and defying authority, with The Catcher in the Rye as a primary influence. Still, the lack of self-awareness turns the whole work into a total farce. How is the player intended to take everything seriously when the plot is full of holes, the characters are problematic, and the entire atmosphere and ethos of the game is overwrought with saccharine melancholy? I don’t, even though most people do because that’s what is intended. Taking Life is Strange seriously results in two reactions. Either people are moved, or people are dumbfounded and pissed off at it. Considering how acclaimed the game became, most people are in the former group, but there has always been a vocal minority in the latter. I’m more in the latter group, but I choose to see Life is Strange for all its positives, for better or worse. It’s my favorite interactive trainwreck trying to convey mid-2010’s teenage angst.

No comments:

Post a Comment