(Originally published to Glitchwave on 10/3/2021)

[Image from igdb.com]

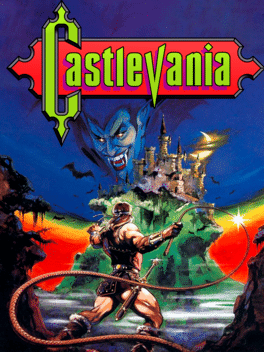

Castlevania

Developer: Konami

Publisher: Konami

Genre(s): 2D Platformer

Platforms: NES

Release Date: September 26, 1986

Castlevania doesn’t just borrow a few elements from the classic monster movies; it’s a game that revels in them. They are the crux of its foundation and the base of its personality. Dracula, the most famous vampire of all time, created by Bram Stoker, is the centerpiece of almost every Castlevania game. In the gaming world, Dracula is as notable an antagonist as Bowser, Ganon, or Dr. Robotnik (Eggman). That’s the extent of Dracula’s place in the Castlevania franchise. Unlike the thin, borderline anemic character played by Bela Lugosi that we’re all familiar with, Dracula is a grand, towering figure like Chernabog from Fantasia donning vampire garb. His castle is also no longer a remote palace accessed through the forest on a dirt trail by horse and buggy. Dracula’s castle in Castlevania is a stupendous tower, the most inescapable thing in one’s peripheral vision at night next to the moon. It’s large enough to be divided into six different levels that make up the game's structure. Simon Belmont, the renowned vampire hunter of the esteemed Belmont clan, is tasked with ascending Dracula’s castle and challenging him in his throne room at the peak of his castle, ending his reign of terror.

Castlevania is also one of the most lauded games on the NES that pushed the console's capabilities. It was released in 1986, only a year after the NES made its international debut. Most if not all of the games during the first year of the NES’s life cycle were rudimentary, to say the least. The graphics for these games were simplistic, with sprites only vaguely depicting what they intended. It was a leap in progress from the amorphous chunks that made up the Atari-2600’s graphics, but the sprites of the first Super Mario Bros and the first Legend of Zelda left much to be desired. The opening sequence of the game where Simon appears at the gates of Dracula’s castle with the monument of horror imposing its presence over him is practically the first cinematic in an NES game.

Once the game begins, the spectacle of the castle never leaves the player. The backgrounds of early NES titles were barely given any detail, probably due to a mix of the elements of the game existing in the foreground and limited capabilities. They were mostly a constant color to portray light or darkness, such as the bright fantasyland land of the Mushroom Kingdom in Super Mario Bros. or the barrenness of space in Metroid. The backgrounds of Castlevania are the colossal walls of Dracula’s gothic estate. If the opening cutscene of the game is any indication, the monumental presence of the castle is something that is felt throughout the game. The game achieves this by consistently offering arguably the most detailed backgrounds of any game at the time. The yard of Dracula’s castle depicts crooked trees in the back with hanging green foliage, and the vestibules of the castle feature wide columns with giant hanging drapes. The interior foundation is cracked out and deteriorated to exude the feeling that this castle has been standing for quite some time. The backgrounds also alternate smoothly between the levels. In the first level, Simon will descend a staircase to find himself in an area near the grounds surrounded by the deep water of the castle’s moat. The background becomes dark to signify that Simon’s outside now, and the water is now a new hazard with fishmen leaping out of it. Linear sidescrollers that made up the early NES library only offered a consistent layout per level with one backdrop. The transitions in Castlevania were something to behold.

Another rudimentary aspect of early NES games was the simplistic gameplay. Many of them still borrowed too heavily from the design philosophy of quarter-devouring arcade games with no continues. This was an inappropriate choice for the home console, and I’m glad Konami felt the same way. Castlevania gives the player three lives with the chance to earn more by increasing the score. A high score is something from primitive arcade games, but it can be excused here because of how arbitrary it is. Frequent checkpoints are implemented in each level to restart the player at a certain point after they die. If the player loses all of their lives and receives a game over, they start at the beginning of the level instead of the beginning of the game. This means of penalizing the player was a more ideal, refreshing change of pace that should’ve been included sooner in NES’s lifespan. Castlevania also implements a health bar so players can get hit multiple times and not die. The player can also find roasts in the crevices of some walls to restore their health. These deviations from the norm seem commonplace now, so I guess I’m not the only one who thought of Konami's acts of mercy here as ideal.

Simon Belmont is also much more readily equipped than most gaming protagonists before him. Like many playable characters from early 2D side scrollers, Simon moves briskly through relatively linear levels with the need to jump occasionally. One might criticize his one jump as it tends to be rather rigid, but the obstacles Simon needs to jump over are never that far apart to pose a problem. His trademark whip also feels somewhat stilted due to its restrained, unidirectional trajectory every time he cracks it. However, I’d argue that this limited range gives the player a concrete understanding of how attacking works, making it easier for the player to acclimate to the controls. Simon can also upgrade his whip by breaking candles that appear all-around each level. The first upgrade will increase the damage the whip deals, and the third, final upgrade will increase its length. Breaking these candles will also give the player extra weapons for Simon to use. The axe is lobbed overhead at airborne enemies, the boomerang covers all ground horizontally to it, the watch freezes time momentarily, the dagger is a forward-moving projectile, and the bottle of holy water ignites the unholy forces of Dracula’s castle in flames. This batch of extra items is far more intricate than the simple Fire Flower projectile from Super Mario Bros. These weapons are activated with the same button as the whip with the additional pressing of “up” on the D-pad. This single-button scheme was only awkward at times when I was climbing up a staircase. To replenish the ammo needed for these weapons, the player collects hearts from enemies and candles. Using hearts as weapon currency takes some time to get used to, I’ll admit.

Thank Christ that Castlevania gives the player enough firepower and gracious room for error because the game is really fucking difficult. Every time I review an NES game, I feel like a broken record talking about how the game represents the phenomenon known as “NES hard,” but it bears repeating with Castlevania. Without the unlimited continues and eclectic arsenal, Castlevania would be unplayable. It’s already an excruciating affair as is. The game expects a lot from the player’s reflexive skills and utilization of the weapons. Replaying each level is a must to get through the game. Bottomless pits are everywhere, enemies will attack the player in vulnerable situations, and the screens will often become hectic with hoards of different enemy types. The reason why all of this is the base of Castlevania’s difficulty is that Simon will get blown back by any hit he takes. I’d be willing to bet that most deaths in Castlevania are caused by getting hit by a bat or Medusa Head and plummeting to their prematurely timed deaths. The saving grace of the difficulty curve is that the game fluidly acclimates the player to it. The first level offers simple enemies that careen toward the player without any tricks while introducing simple platforms to jump over. The second level introduces the notorious medusa heads that, while moving in a consistent pattern, manage to catch even the most seasoned of players off guard. The third and fourth levels are filled with bottomless pits and enemies that run around erratically.

The bosses of these levels also follow the same difficulty curve. This array of spooky, classic monsters also gets progressively more difficult. The bat and Medusa can be shredded by the whip in no time at all while fighting against the mummies and Frankenstein’s monster with the additional hunchback (Yes, these things are hunchbacks, not monkeys. It’s kind of hard to tell because of the graphics, but the reference to Igor the hunchback fighting with Frankensteins’ monster makes more sense) can be hectic due to being cramped on a stage with two boss enemies. The fifth level is a culmination of escalating difficulty and one big roadblock. This level does not mess around. Suddenly, the game includes the durable knight enemies and scatters them all over the place. The hallway before the boss of this level forces the player to confront three of these enemies with a constant stream of medusa heads flying around. The player’s accuracy has to be dead-on to survive, also staying conscious of their level of health for the boss. The formidable foe at the end of this hallway is Death himself, the scythe-wielding Grim Reaper. He’s about as hard as you’d imagine fighting the personification of death would be: practically fucking impossible. Even if the player defeats him, his rotating scythes remain and can still kill players that survived by a minuscule health strand.

The developers may as well not have programmed another level after this one because I’d imagine most people haven’t surpassed it. For those few who have, a spellbinding fight with count awaits them. The platforming section before his fight is simple enough, but the player has to endure a tedious grinding section to fill up on hearts outside of his quarters. Trust me, it’s essential in beating Dracula. This doesn’t apply to his first form, as his patterns are simple as long as he doesn’t appear in front of the player. His second form is the reason for the grind session. His head comes flying off as he unsheathes his robes to reveal an indescribable demon. This phase does not subscribe to normal amounts of health as it seems five to six hits deplete one block of health here. This usually results in the player frantically alternating between the whip and the holy water with an added force of prayer on the player’s side that the ugly demon will die. Once he does, Simon is victorious, and Dracula’s prodigious castle crumbles to the ground.

The golden age of horror films may not be as effective as they were during their heyday at providing scares. That does not mean that the general properties of these films are ineffective in being fun and entertaining. The NES classic Castlevania put Dracula and the rest of these horror relics back into the limelight in a completely different medium. The spooky, grandiose halls of Dracula’s castle are treated with arguably the best attention to detail the NES could offer. Dracula reignited his role as a supernatural, imposing force of evil by providing some of the starkest challenges in his gothic manor in gaming and being the tense climax of all of it. All of these factors constitute a solid early NES title ahead of the curve in many ways, making it one of the shining examples of the system.

No comments:

Post a Comment